If you’ve ever sat through a meeting that wandered, tangled itself into knots, or left half the room wondering what they just voted on, you already know why parliamentary procedure exists. It isn’t about silencing people or creating red tape. Used well, it helps a group make clear, thoughtful decisions without wasting anyone’s time.

I recently recorded a short video walking through the basics. You can watch it here if you prefer video over reading:

What follows is a revised, reader-friendly version of that material, shaped especially for the organizations I advise. If you prefer reading over video, this is the best way to get this material.

What a Parliamentarian Actually Does

A parliamentarian has no authority to run a meeting. None. Zero. The presiding officer is always the one directing traffic. My role as a parliamentarian is to advise so the chair can guide the assembly smoothly. All real power rests with the assembly itself, which is why understanding the rules helps everyone participate more effectively.

Why Parliamentary Procedure Exists

Parliamentary procedure is designed for deliberative assemblies, groups of people making decisions together. Contrary to the popular stereotype, the purpose isn’t to shut people down but to balance two needs:

To hear everyone who has something meaningful to contribute

To move business along efficiently

Every rule in Robert’s Rules of Order, Newly Revised (RONR) supports one or both of these needs.

Too much emphasis on discussion produces aimless meetings. Too much emphasis on efficiency produces autocracy. Procedure helps find the middle ground where good decisions happen.

Which Rules Matter Most

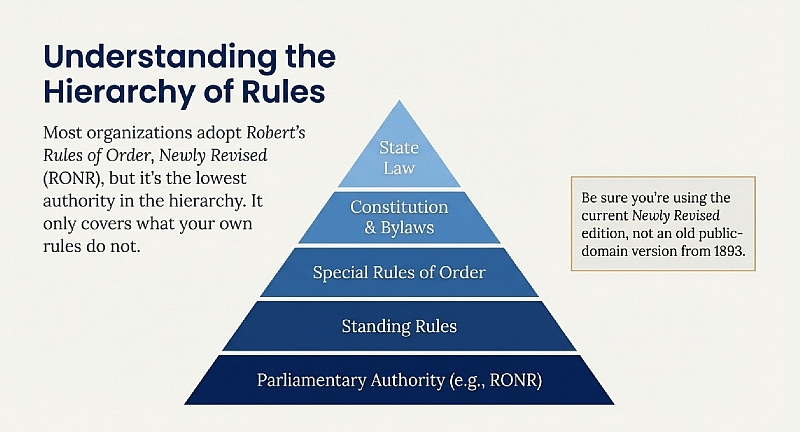

Most organizations adopt Robert’s Rules of Order, Newly Revised as their parliamentary authority. It acts as a ready-made rulebook. But keep this in mind: RONR is the lowest authority in the hierarchy. It yields to:

State law

Your constitution

Your bylaws (most organizations collapse constitution and bylaws into one document)

Any special rules of order

Standing rules

Only after those do rules of order kick in. In essence general rules of order cover anything not covered by any of the above.

If you own an old, cheap edition of “Robert’s Rules,” it’s probably the 1893 public-domain version. Interesting historically, but not authoritative.

The Heart of It All: Motions

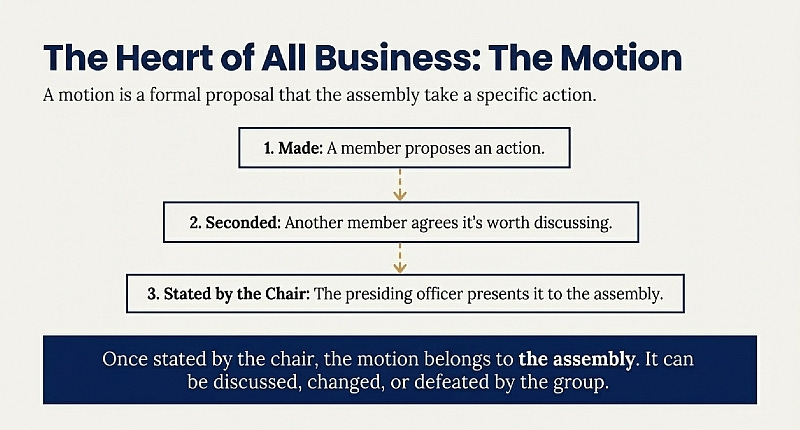

A motion is a formal proposal that the assembly take a specific action. Once a motion is:

Made

Seconded

Stated by the chair

…it belongs to the assembly, not the person who made it.

This protects the group’s right to discuss, amend, or defeat the proposal.

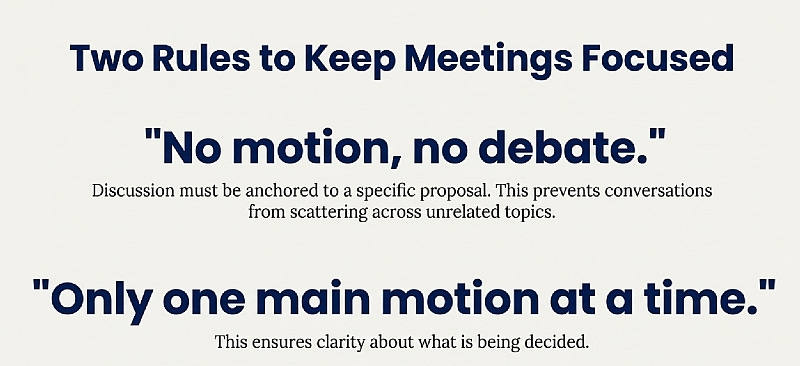

No motion, no debate

Discussion must stay anchored to a motion. This keeps meetings from scattering across unrelated topics.

Only one main motion can be on the floor at any given moment. This rule exists because without it, confusion reigns. In fact, I once survived a five-hour faculty meeting where, after a vote, someone asked, “Wait… is that what we were voting on? I thought we were voting on [something else].” The discussion restarted from scratch. Don’t be that meeting.

Secondary Motions: The Supporting Cast

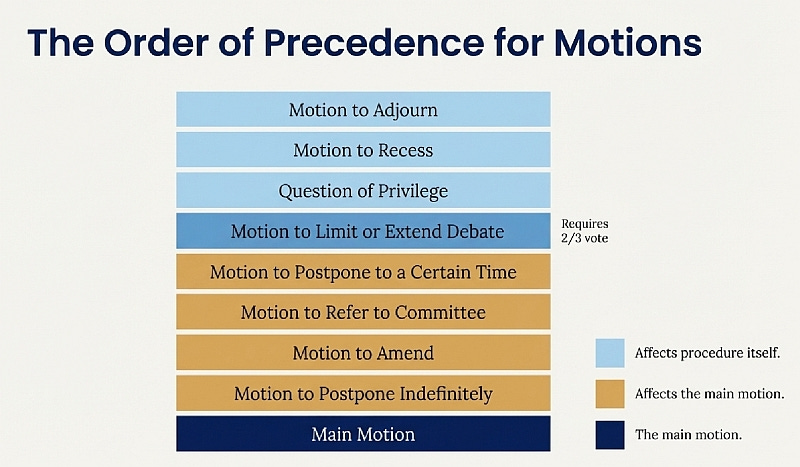

Secondary motions help shape or control debate. They include things like amendments, referring a matter to committee, or limiting debate. These motions follow a strict order of precedence.

When someone says “Your motion is out of order,” it usually means a higher-ranking motion is already on the floor, not that there’s anything improper about the person making it.

A key distinction:

Some motions affect the main motion (amend, refer, postpone).

Some affect procedure itself (limit debate, call the question).

Most allow discussion. Some require an immediate vote. Most pass by majority. A few require two-thirds, especially those that limit members’ rights (for example, ending debate).

You can get a detailed chart that tells you a lot about specific motions here.

How Voting Really Works: Majorities and Abstentions

“Majority” means more than half of those present and voting. Abstentions do not count against anything. They simply reduce the total number of votes.

Example:

If 100 people are present and only three vote, with two in favor and one opposed, the motion passes. Ninety-seven people declined to shape the outcome (saying, in essence, they were OK with either outcome), so the ones who preferred an outcome decided it.

Some motions require a majority of the entire membership or of those present, but those are exceptions and clearly specified.

What a Second Actually Means

A second doesn’t mean support. It means the member thinks the motion is worth discussing.

RONR adds this practical point: if debate begins even without a formal second, the motion is considered automatically seconded. The assembly has already shown interest by engaging it.

The secretary records who made the motion, but not who seconded it.

Amendments: How to Change the Wording

You can have:

The main motion

An amendment to the main motion

An amendment to the amendment

…and that’s it. No third-level amendments.

Example:

Motion: “Send out for pizza.”

Amendment: Add “pepperoni” before “pizza.”

Amendment to amendment: Add “and sausage” after “pepperoni.”

When you discuss amendments, all you’re debating is whether to change the wording of the main motion. If amendments pass, the group still must vote on the main motion—in this case, whether to send out for pepperoni and sausage pizza. Amendments only change wording, not the final decision. This is to maintain clarity about the subject under discussion.

Unanimous Consent: The Shortcut That Isn’t a Vote

When an item seems noncontroversial, the chair may say:

“If there is no objection, we will… [take the action].”

Pause.

If no one objects, it’s adopted. If even one person objects, the group returns to formal procedure. The objector doesn’t need to be against the action, only in favor of discussing it.

Unanimous consent keeps trivial matters or even important matters with no disagreement from consuming time.

A Word About Debate: Balance Matters

When debate occurs, a good presiding officer alternates between speakers for and against the motion to give the assembly a balanced view. Your officers receive training in these practices so the group can make its best decisions.

And if you ever feel unsure about how to make a motion or what’s happening in the procedure, ask. Clarity is everyone’s friend.

In Closing

This isn’t everything there is to know about parliamentary procedure, but it’s enough to help you participate confidently. The rules exist to help you hear one another, make thoughtful choices, and leave meetings with clarity rather than confusion.

Questions? Email donnell.king@gmail.com.